I recently read James, Percival Everett’s story about the runaway slave, Jim, who accompanied Tom Sawyer down the Mississippi River. The story is told from the slave’s perspective which gives Everett many opportunities to reveal the slave’s character.

The most remarkable thing about this story is how Everett portrays Jim as a well-read and highly literate man, not mentally bound by the psychological chains of slavery. Instead of being illiterate, he is able to effectively communicate ideas, can understand complicated information, and is capable of critical thinking.

Ability to Read and to Understand Complicated Subjects

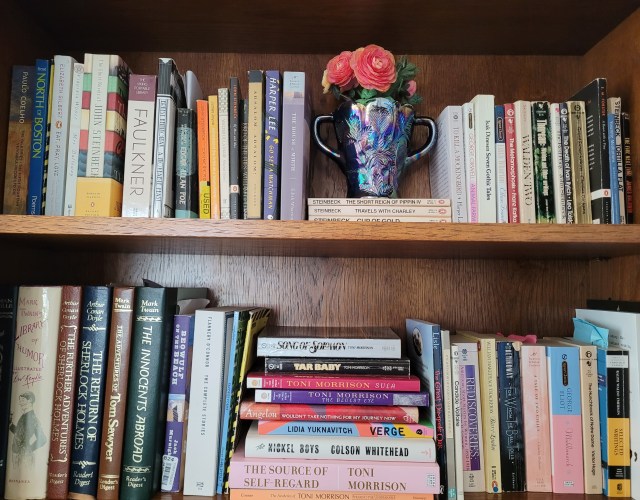

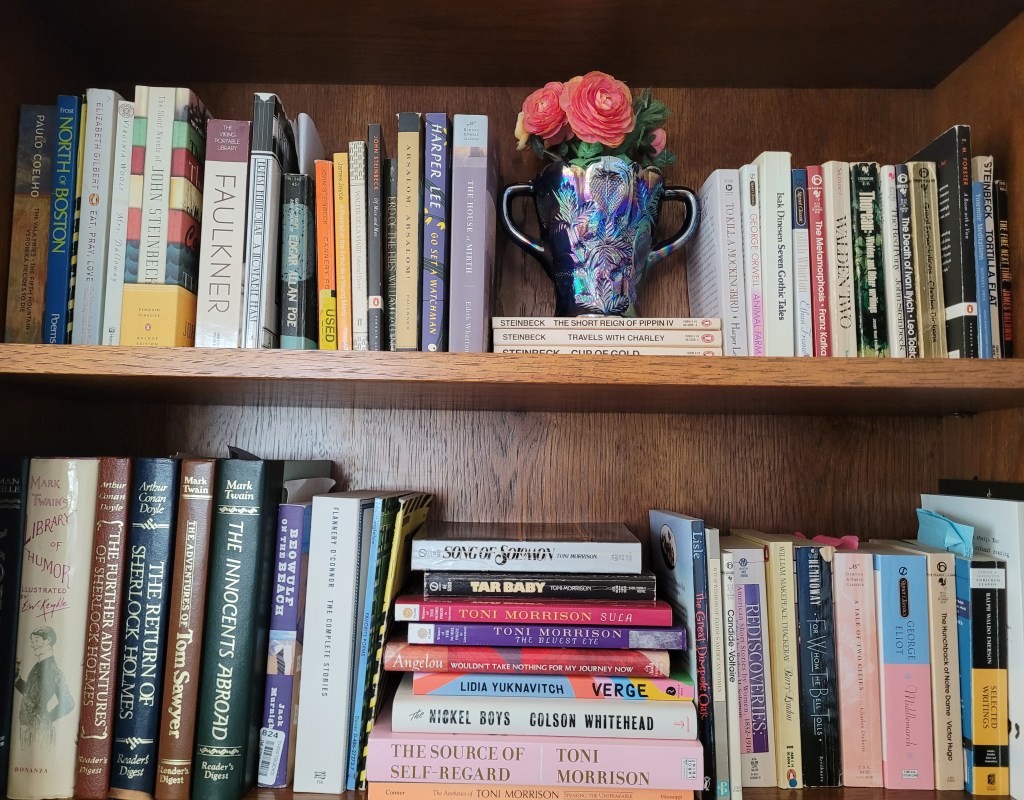

Early on in the story, the reader learns that Jim has taught himself to read by studying the books in Judge Thatcher’s library. In addition to learning how to read, however, he also has developed the ability to think about complicated subjects such as civil liberties and how the morality of religion conflicts with the concept of slavery. He has read the literature of philosophers such as Voltaire who advocated for civil liberties through freedom of speech and freedom of religion and has seen texts by John Stuart Mill who wrote about individual liberties. We also learn that he knows of the works of Rousseau and John Locke, both of whom influenced the French and American Revolutions. Jim proves his literacy and ability to think about complicated subjects by contemplating the differences between being enslaved or possessing individual rights.

Awareness of the Effects of Various Language Skills

Before Jim runs away,he teaches his daughter and other slave children the difference in speaking like a slave and speaking like a literate human being. He cautions them to never make eye contact with a white person, never speak first, or ever to broach a subject directly with another slave since these are the behaviors of someone who is confident about their opinions. In fact, he teaches them not to express opinions of any kind and to let the whites identify any problems that come up.

He coaches them on using poor pronunciation, incorrect spelling. The goal is to make the whites think that blacks are stupid and that they can’t express themselves clearly. This puts the whites in the position of feeling superior and protects the blacks from being blamed for trouble. What is made abundantly clear, however, is that Jim and the children he teaches are capable of distinguishing between the language that keeps a person subservient and a language that empowers them.

Ability to Write

At one point in the story, Jim asks a slave to get him a pencil so he can write. Young George steals a pencil from his owner, gives it to James, and eventually loses his life because of his “crime.” However, James keeps the pencil in his pocket, the safest place he can find to avoid losing it. The pencil represents his ability to write down his own ideas, one of the most empowering aspects of being a literate person.

Use of Literacy to Make Better Decisions

Jim’s literacy allows him to make better decisions about how to survive. At one point, since he knows he’s being searched for under the name of “Jim,” he tells a white man, Norman, to call him February, but to say that he was born in June. If he hadn’t been able to read, he’d not have known the order of the months or how to manipulate them to help save his own life. When he returns to Judge Thatcher’s library, he forces Thatcher to show him how to use the map to find the farm where his wife and daughter are living.

Jim wouldn’t have been successful at escaping slavery without his literate skills. His literacy allows him to communicate with people he meets, analyze his predicaments, and form judgments about how to survive. In the end, when the sheriff asks him if he is Nigger Jim, he elevates his name to the more formal version, James. After all, he is no longer the slave that was once given the name of Jim.