Photo by Kirt Morris on Unsplash

I was fifteen years old when my father went to war in Vietnam, not old enough to understand the news or to pay attention to adult worries. But I remember my dad standing at the front door with my mother hanging onto him, tears streaming down her face.

When my dad came home, we expected that he’d sit in his big armchair set in a corner of the living room, gather his children around his feet, and tell stories about what he saw. But he didn’t. He sat in his armchair, staring at the blank television with furrows in his brow for hours each night after work and during the long afternoons on the weekend. We crept past his chair silently afraid of his morose temperament.

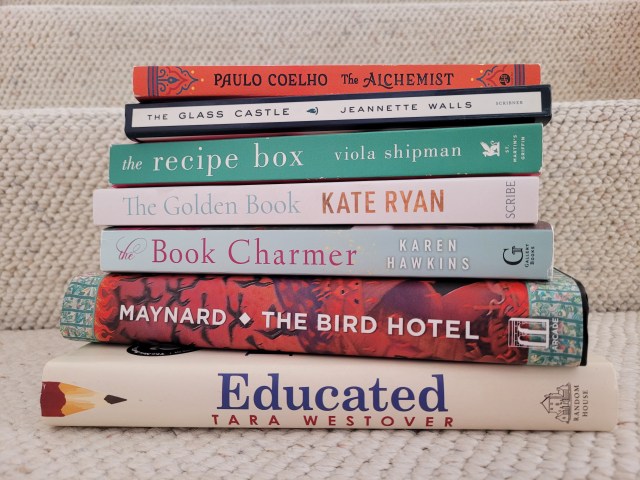

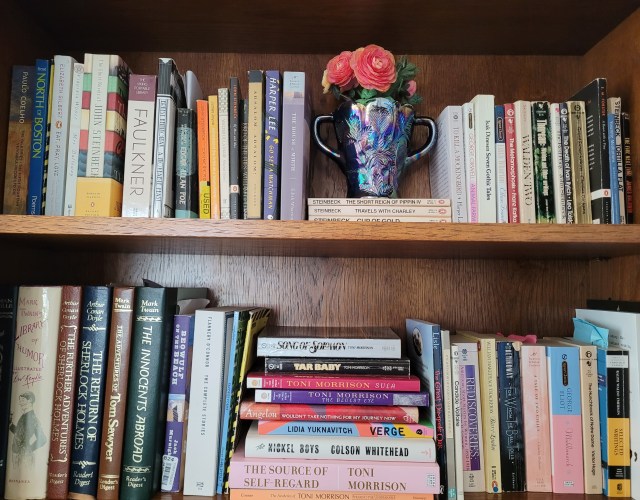

When I discovered The Women by Kristin Hannah, I thought it would be an opportunity for me to learn about my father’s Vietnam experience that he never shared with us. The book tells the story of a young woman, Frances Grace McGrath, who becomes a nurse and signs up to serve in the army in Vietnam in 1965. She joins the Army Nurse Corps since the Air Force and Navy require her to have more clinical experience than she has.

Frances, known as Frankie, is inspired to sign up for service because her father has a wall in his study of the family’s military heroes, and she wants to be on that wall. The only woman on the wall is her mother in a wedding picture. Just before her brother leaves for the war, one of his friends tells her that women can be heroes, too.

My father, on the other hand, tried to avoid going to Vietnam. By 1965, he had been in the Air Force for twelve years and was a senior flight mechanic, a valuable skill for a war being fought with helicopters and airplanes. 1965 was the year that President Johnson increased troop deployment to Vietnam and began direct combat operations to shore up the South Vietnamese defense against the communist Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces. My father petitioned not to be sent, so he was deployed instead to Mildenhall, a U.S. Air Force base in the United Kingdom. I was only nine years old. The bad news was that he had to leave his circle of friends in California to serve there for almost four years. The good news was that his family could join him, his wife and all nine kids. We came back to California in 1969. But this alternate deployment did not protect him from being shipped off to Vietnam.

In 1972, when the war was raging and tempers were flaring at home about it, I still didn’t know much about the war even though I had seen pictures of U. C. Berkeley students protesting it on television.

In April 1972, my dad closed the front door on his family and flew to serve at Cam Ranh Bay, an air base Vietnam used for the offloading of supplies, military equipment, and as a major Naval base. My father was assigned to serve as the senior flight mechanic on a huge transport plane known as a C-5B, a plane that can transport a fully equipped combat unit with oversized cargo. He wrote numerous letters home. In one, he writes about how he sprained his ankle in the shower. In another, he describes how a bomb went off outside the plane, the noise ringing in his ears.

I know my father took soldiers to the front lines and brought home dead men in body bags. He didn’t tell us that, but when I read about the use of C5-B planes, that’s what I learned. I know also that the planes were used to rescue Vietnamese women and children and bring them to the United States. Once, my father described how they had to shut the cargo door to keep out the hordes of civilians trying to board the plane.

After my father died and I was helping my mother with his estate, I came across some paperwork relating to a lawsuit about Agent Orange. Apparently, my father had been exposed to it in Vietnam. I had heard of it and thought that it was some kind of chemical used in a war. In The Women, I learned that it was a deadly herbicide used to kill jungle foliage to prevent the Viet Cong from hiding. Exposure to it causes cancer, birth defects, and other illnesses. My father died when he was 76 years old from heart trouble. His grandfather had lived to the age of 98 years old. Could he have lived longer if he hadn’t been exposed to Agent Orange?

Dad only stayed in Vietnam for eight months. He came home early since President Nixon had decided to withdraw U.S. troops by January 1973. Dad flew into Beale Air Force Base and my mother rushed to see him as soon as he landed.

By 1972 in the book, Frankie is home, experiencing nightmares and guilt for being part of a war that Americans didn’t want. She had seen soldiers without limbs, chest wounds, and mangled heads. They haunted her in her dreams, and when loud noises went off around her, she ducked for cover.

I don’t know if my father had nightmares like Frankie. I don’t know how the war protesters made him feel. Unlike Frankie, whose military service was ignored by her family and country, I think my father had emotional support waiting for him at home. My parents had a large community of friends in their church, who rallied around him when he returned. Finally, after months of grim silence, he got out of his armchair and settled into life again. A few years later, he retired from the Air Force and went back to school to get his contractor’s license. His last job was building candy stores for See’s Candies.

Frankie’s story taught me how the women who served in Vietnam received little or no credit for their valor even from their own families. As a woman, I’ve experienced a lot of inequality, so the story affected me deeply. But as the child of a soldier in Vietnam whose life was profoundly affected by a parent’s suffering, I’m thankful that it uncovered some of the mystery of my father’s Vietnam deployment.