Wouldn’t it be a better world if everyone knew what they needed to be happy? I’m retired, and I loved my teaching job; however, now that I don’t have to commute to work five days a week or grade college essays on the weekends, I just want to do things that make me happy. Here they are.

Admiring Flowers

Stopping to smell a rose may seem like an unimportant action, but, when I do it, it brings me joy. I have rose bushes in my front yard and back yard, and every morning, I wander outside to inspect every bush to see the new blooms. I sniff and stare and smile to my heart’s content.

I remember the flowers of my childhood, too. In January, crocuses poked out of the soil in the flower beds in the front yard. In February, the daffodils came. Tulips arrived in March, and Irises after them. By the time Lent was over, Easter Lilies grew like sophisticated ladies in white hats in our back yard. And in May, the meadows were carpeted with Bluebells.

For four years of my childhood, I lived in England with my family, and I was impressed by the colorful blooms of summer that thrived in the temperate climate. Rambling roses climbed up cottage walls. Cosmos waved their rainbow heads in the breezes like pretty bonnets. Hydrangeas brightened shady nooks of gardens with their puffy burst of blue and pink. I was entranced by their beauty.

At Christmas, my mother bought at least one Poinsettia to decorate the house. She bought red poinsettias, white poinsettias, and ones with white flowers with red stripes. Sometimes, she had an amaryllis bulb growing in a pot. Every day, I’d inspect it to see whether it was blooming or not. I was in more of a hurry than it was.

Making a Stew or Pot of Soup

Whenever my dad cooked, he made “water” soup. He added pieces of beef and vegetables to a pot of water to create soup. Ugh. We kids would cringe when we saw him taking out a pot. His were the worst soups I’ve ever tasted.

Maybe that’s why I love making delicious soups.

I own an old Dutch oven that is the perfect size for making one-pot meals. Some mornings even before I change out of my pajamas, I scour the refrigerator and pantry for the ingredients for a minestrone—onions, celery, carrots, zucchini, chick peas, barley, chicken broth, chopped tomatoes, oregano, salt, and pepper. Sometimes I add cooked shredded chicken. Often, I don’t.

Or I find the fixings for chicken noodle soup for a recipe from a William’s Sonoma Soups book that I bought a long time ago. While I’m chopping the carrots and celery for this soup and simmering the chicken breasts in the broth, I think back when I made this for my two children who loved it. I see their little faces above their steaming bowls, their hands holding spoons, their mouths filled with savory egg noodles.

On one European trip, I bought cookbooks in the Czech Republic and Austria, so when I want to make goulash, I search for recipes from those books. My favorite goulash is a beef, onion, and smoked paprika concoction that is topped with cornmeal dumplings. I first ate cornmeal dumplings at the restaurant at the Belvedere Palace Museum in Vienna. I’m still practicing to make mine taste as good as those were.

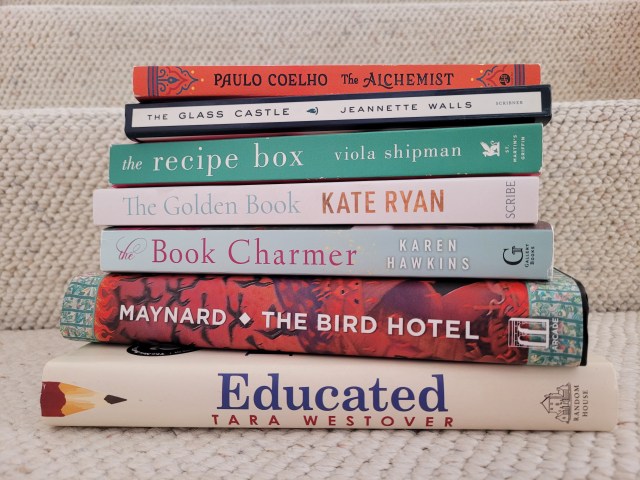

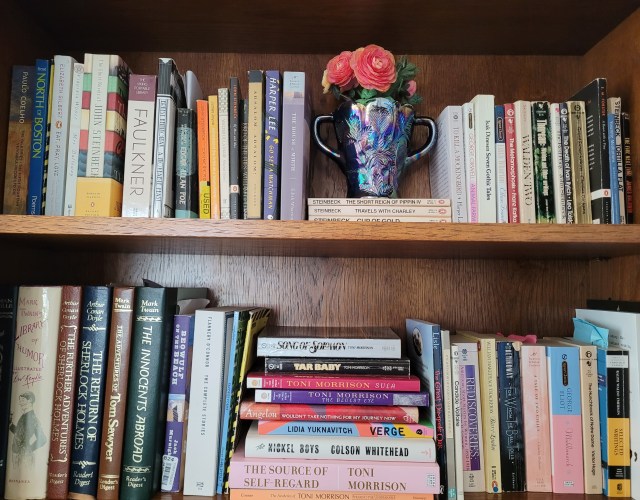

Reading Inside When It’s Cold Outside

To me, the essence of decadence is waking up in the morning, seeing that it’s cold and rainy outside, then reaching for a novel and reading it in bed. To take all the time in the world to read a story, then stopping and thinking about it is heaven on earth.

Reading when its cold outside reminds me of when I read as a child. I had time to sit on the floor in a corner of the house with a treasured book of fairy tales and get lost in another world. When my mother took me to the open-air market, I found the bookstore, walked to the back shelves, pulled out a tome, and read it while sitting on the floor. I was always afraid that the shop owner would find me and kick me out, but he never did.

Decorating My Home

When I was a child, we never had an expensive home, but that didn’t keep us from making it beautiful. In the spring and summer, I picked flowers in the meadows, poked them into vases and brightened every table and dresser in the house. In the fall, I cut branches of colored leaves for the mantel in the living room. For winter, my mother and I found pine cones and spray-painted them silver and gold for Christmas. We added holly and pine branch garlands in-between them.

Today, when a new season comes, I still have the irresistible urge to celebrate it with seasonal décor. Right now, I have a collection of pumpkins on my front porch accompanied by a little witch. I also have put pumpkins on the table on the back patio so we can feel the season when we go outside in the afternoons. Every time I pass these decorations, I feel like celebrating.

Writing

I wrote my first poem when I was nine years old, and I’ve been writing ever since. Sometimes, I use writing to help me sort out a problem. Currently, I’m the chair of a scholarship committee for a charitable organization. When I’m planning the meeting agendas, I write them to organize my thoughts. When I’m thinking about how to improve my author’s platform, I write my thoughts down. I write down daily affirmations and New Year’s Eve resolutions. I write every day.

Even when I’m traveling, I have a journal that I use to take notes or write a spontaneous poem. I remember one vacation that I took by myself to Boston. After I toured Paul Revere’s tomb and all of Boston’s historic sites, I drove north up the Atlantic coast. I stopped in Salem and visited another graveyard where a huge oak tree that had gotten so big over the centuries that tombstones were poking out of its bark halfway up. There was so much to write about. Finally, I stopped the car at the edge of the road near a beach. As I sat in the sand and gazed over the surging navy-blue sea, I wrote a poem about the peace that I felt.

When I visited Sorrento, Italy, I stayed in the Grand Hotel Excelsior Vittoria. Our room had a large terrace that overlooked the Sorrento Harbor. Across the Bay of Naples with its slate-blue ripples, we could see Mount Vesuvius. Every day, I sat at the patio table on this terrace with my journal to write about the gorgeous scenery or about my excursions into the town of Sorrento or its nearby attractions. I wrote how my husband had to scrunch down going into the Blue Grotto Cave in Capri. I described the ceramic factories that we toured in Almalfi. With words, I wondered what it was like to be a citizen of Pompeii in 79 AD when Mount Vesuvius spewed its lava all over the populated city.

Now that I think about it, I’ve been doing these happy things my whole life. Naturally. Now, though, I have more time to do them. What joy.